The below resources are for educators, students/trainees, and others interested in materials that help explain and distill concepts pertaining to antimicrobial resistance, One Health, and more. Please feel free to use these resources in your courses or share them to your websites and social media. We only ask that you link back to us at www.LevyCIMAR.org when you do. You can email us with any questions at CIMAR@tufts.edu.

Antimicrobial Resistance and Inequality

Antimicrobial-resistant (AMR) infections can be deadly, and can impact anyone without discrimination including the young and otherwise healthy. “Superbugs”—or disease-causing bacteria that are resistant to treatment—are found in all regions of the world including right here at home in the United States. Resistant bacteria can be found in our food and all around us, including in our own bodies. This can be bad news for our health.

But AMR has even more far-reaching consequences that are often overlooked, and some of the most vulnerable groups in our society, including racial and ethnic minorities and the economically disadvantaged might be most at risk. Global changes in climate, urbanization, food production, and income inequality threaten to worsen these disparities.

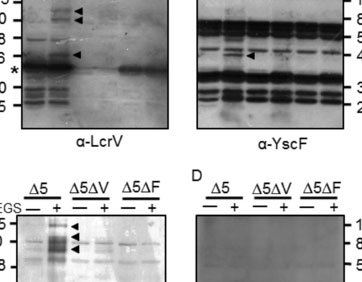

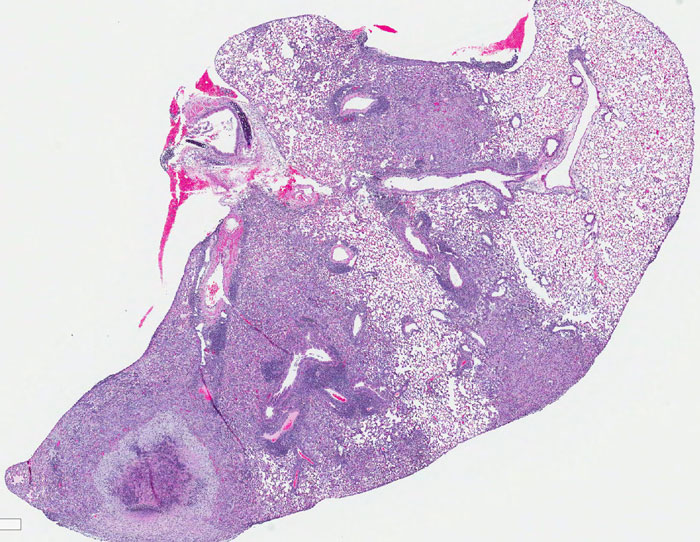

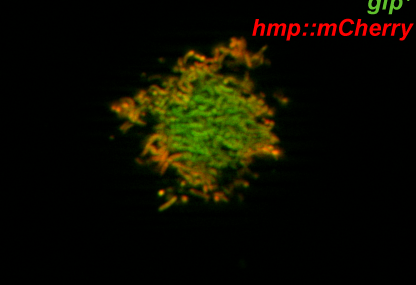

The following infographics explain both how resistance emerges and spreads, as well as how it might impact marginalized communities more than the average person.

|

|

|

|

The above information on AMR and Inequality was written by the Levy CIMAR’s Maya Nadimpalli, PhD, whose work involves using genomic and epidemiological approaches to understand how exposures to food, animals, and the environment can impact human colonization and infection with antibiotic-resistant bacteria, particularly in low-resource settings. The infographics were designed by Dr. Nadimpalli and Madeline Verbica, curriculum illustrator for Great Diseases.

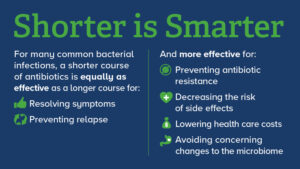

Shorter is Smarter

Credit: Tufts Medical Center, Shira Doron, MD, and the Levy CIMAR. Click to expand.

Many people look to their doctor for everyday health needs, including treatments for common bacterial infections, such as a sinus or urinary tract infection (UTI). But while the antibiotics prescribed may help you in the short term, a longer course may cause resistance or other unwanted long term side effects.

Antibiotic overuse has become a key factor in antibiotic resistance, which has become a global crisis. Yet research shows that primary care physicians prescribe antibiotics in 10% of all outpatient visits. And the longer the duration of antibiotics for common bacterial infections like a UTI, the more likely that antibiotic resistance will develop. We asked the Levy CIMAR’s Shira Doron, MD, Infectious Disease Physician and Director of Antimicrobial Stewardship at Tufts Medical Center, how to know if you are being prescribed the appropriate antibiotic duration and how to avoid developing antibiotic resistance.

What is the appropriate duration of antibiotics to be prescribed?

The dosage of antibiotics may vary based on the infection and the antibiotic but a new guideline offers best practices on prescribing shorter-course antibiotics for some common infections.

Although there are exceptions for specific clinical factors, typically, a recommended 5-day antibiotics course applies for these four infections:

- Acute bronchitis with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation

- Community acquired pneumonia (CAP)

- Urinary tract infections including uncomplicated kidney infection- could be as little as a single dose depending on the antibiotic

- Cellulitis (skin infection)

Credit: Tufts Medical Center, Shira Doron, MD, and the Levy CIMAR. Click to expand.

Is a shorter dose of antibiotics just as effective?

A shorter course of antibiotics for many common bacterial infections has been found to be just as effective – and in many ways, a smarter choice — than a longer course of antibiotics.

How do I talk to my doctor about whether the duration of antibiotics prescribed are appropriate for me?

Patients and doctors share the responsibility of antimicrobial stewardship. When your doctor prescribes an antibiotic, ask whether the recommended duration is as short as it can safely be. Also inquire as to whether you should “finish the prescription” even if you feel better, as prolonged antibiotics courses have just as much risk of creating resistance as too short a course. And remember: appropriate antibiotic use means prescribing the right antibiotic for the infection, in the right dose, for the right duration – every time.

The above information on “Shorter is Smarter” comes from Tufts Medical Center (TMC) and the Levy CIMAR‘s Shira Doron, M.D., TMC Director of Antimicrobial Stewardship, Attending Physician, and Hospital Epidemiologist. If you plan to use any of the materials from the “Shorter is Smarter” section, please credit and link back to us.

Funding Opportunities for Graduate Students and Post‐Doctorates

Each summer, our Center offers financial support for a limited number of summer internships for undergraduate students from groups traditionally underrepresented in the biomedical sciences. You can learn more about the The Stuart B. Levy CIMAR Undergraduate Summer Internship for Underrepresented Groups in Science and Medicine here.

This document (.PDF) highlights several websites, databases, and other resources where graduate students and post-doctorates can find funding opportunities through Tufts University, as well as from the federal government, philanthropic foundations, and corporations.

The document also includes tips for finding the right opportunities and helping ensure one’s success when applying. Members of the Tufts community can find additional resources through the Tufts University Office for Corporate and Foundation Relations (CFR) website. CFR offers assistance through all stages of the proposal process.